Are the distinctive feet of Bolitoglossa Salamanders the result of natural selection? We covered this information in the last newsletter, but to summarize:

- We originally believed that salamanders in the genus Bolitoglossa evolved “suction cup feet” under natural selection for arboreal habitats.

- However, Arboreality evolved multiple times in Bolitoglossa and there is evidence the rate of transition was 24x higher for terrestrial lifestyles.

- Finally, they found no meaningful difference in foot morphology for arboreal or terrestrial taxa.

Ultimately, we accepted these feet may not be an adaptive trait. But then the question remains, Why do Bolitoglossa salamanders have such distinctive feet?

The Spandrels of San Marco

If you visit St. Marks Basilica and look up at the arches, you will find spandrels. These are support structures which maintain those very arches. If you look a bit closer, you will find them adorned with an elaborate mosaic depicting stories from Christianity.

Naturally, the art is structurally functionless. It is not the thin veneer of paint nor the etched figures holding up the stone arch. It is the spandrel itself!

The classic paper “The Spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian Paradigm: A Critique of the Adaptationist Programme” from Gould and Lewontin was inspired by those very Spandrels in St. Marks Basilica. In it, they caution evolutionary biologists to not immediately assign adaptive function to all visible traits.

In other words, don’t think the art is holding up the arch.

With our Bolitoglossa, there were already ~250 papers published before the Spandrels Paper in 1979. Even after its publication, it still took decades for this caution to take foothold in the scientific community. Even then, the prevailing way evolution is taught is under a purely selective lens. One only needs to enter a Bio 101 lecture to see how “Survival of the fittest” is the default explanation for near every adaptation.

In the 2019 paper, the authors found that foot morphology was neither positive nor negative over millions of years of evolutionary history. In doing so, we find they are a class example of a spandrel – a distinctive feature thought to be a signifier of adaptation.

In reality, it was a distraction.

However, just because we know its a spandrel that still begs the question. Why do they have these distinct feet?

Back in 2007, Jaekel and Wake published this paper providing early evidence for the lack of adaptive signal for webbed feet. However, they did determine the degree of webbing was higher in the Bolitoglossa genus. And they came up with a rationale reason.

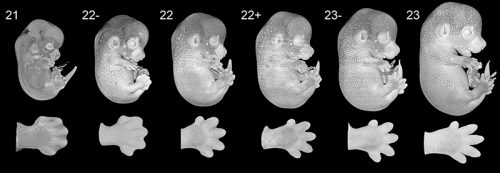

During development, one of the final stages for most tetrapods is the reduction of webbing. We can see an example for this in mice below.

Unlike mice, our salamanders are ectotherms. Their metabolic and developmental properties are influenced by the temperature around them. The higher the temperature, the faster each of these processes work.

Bolitoglossa salamanders have their origin in temperate North America. Their ancestors lived in the Appalachians with much cooler temperatures. Over several million years, those ancestors dispersed southwards into Central America, following the mountaintops of the Sierra Madre Oriental. As they progressed closer to the equator, the temperature increased.

The prevailing theory is that these salamander feet are a paedomorphic trait, meaning some trait representative of a juvenile state. The increased temperatures hastened their development, resulting in adult salamanders that possess webbed feet.

Think of it like having the temperature too hot in the oven. You put your biscuits in and take em out when they look perfect. But when you take a bite, you discover the center is still raw.

Of course, it is entirely possible these ancestors derived some benefit from underdeveloped feet that is lost on its ancestors. It could also simply be that there were some other benefit to being paedomorphic (faster development time, less resources etc.) and the feet were a side effect.

Or it could simply be that there is no adaptive benefit or consequence at all 🙂

That concludes our evolution mini-series! Sorry it took so long! I’ve been working hard on the rebuild of Learn Adventurously and the launch of the Learn Adventurously Bioclub (The LAB). Next week, we have our first webinar on “How to clean biological data with tidyverse”, exclusively for LAB Members.

For this newsletter, you can expect these emails to hit your inbox weekly again! While I announced the migration to Substack, there were numerous issues I discovered with the platform that led me to nix the migration. In response, i’ve moved all my old newsletters into individual blog posts on Learn Adventurously. I’ll be bringing you a new topic next week!

See you soon Biologists,

-D